Voting Systems

Voting in politics and in software applications isn't as simple as it may seem. Here I discuss designing some basic voting systems and analyze their intricacies, pros, and cons.

Introduction

We encounter voting in some form around us all the time. We rate our Uber drivers, they rate us back. We up-vote and down-vote posts and trolls on Reddit. We give stars to movies and restaurants. We vote on who gets kicked out of our favorite reality television show. We vote for Presidents.

All these voting systems seem a bit different from one another, but one thing that's definitely common among them — we will find ways to complain about them. The way a voting system is designed can make an election trivial or really complicated in nature. In fact, sometimes, the winner of an election may be determined by the rules of the voting system and not the intent of the voters (electoral college anyone?). In this post I try to explore the core of different voting systems and wonder if there is a perfect voting system.

Here I am going to use the word election to define an event or a goal that requires voting. An election doesn't have to be political in nature.

Note and Acknowledgement: This blog post is influenced by the chapter on voting systems in video games in the book Power-Up by Matthew Lane.

Plurality Voting

This is the simplest form of voting. Most political elections in the United States are done using this form of voting. It's quite simple — every voter casts a vote for their favorite candidate. The candidate with the most number of votes wins.

Let's look at an example that we will continue to use in this post. We ask 100 people to vote for their favorite flavor of ice cream. The candidates are Vanilla, Chocolate, and Strawberry. Here's the result:

| Flavor | Votes |

|---|---|

| Vanilla | 45 |

| Chocolate | 40 |

| Strawberry | 15 |

Vanilla has won! Now if you stare at the numbers a bit, you will find some downsides in declaring Vanilla the winner in this election of the flavors.

An obvious one is that more votes were cast for a flavor that is not the winning flavor. You could also argue that no flavor should win because none of them reached a majority.

Here Strawberry is acting as a spoiler — similar to how third-party candidates in US elections can be considered spoilers. Maybe we should have a run-off election where only Vanilla and Chocolate are considered. Perhaps more people favor Chocolate over Vanilla when Strawberry is out of the picture. (The US state of Georgia has rules akin to this. In the 2020 elections for the senate seats in Georgia, none of the candidates achieved a majority. So run-off elections will be held in January of 2021 with the top two candidates).

The essence of the Plurality voting system is that it does not capture the full spectrum of voters' preferences. If someone voted for Strawberry, it does not tell us how they feel about Vanilla or Chocolate.

This system does not truly determine the 'will of the people', unless.... there are only two candidates. One of the candidates is guaranteed to receive a majority, barring a tie. So if it were truly a two-party system some of the flaws of this system do not matter any more.

Ranked Choice Voting

Since the Plurality based system does not capture the full spectrum of the voter's preferences, we should probably ask for more information from the voters. What if we asked the voters to rank all the candidates, rather than cast a ballot for their favorite?

Let's look at the example we've been working with. We asked the 100 people to rank the candidate flavors. Here's the result:

| 1st | 2nd | 3rd | Votes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Vanilla | Strawberry | Chocolate | 45 |

| Strawberry | Chocolate | Vanilla | 15 |

| Chocolate | Strawberry | Vanilla | 30 |

| Chocolate | Vanilla | Strawberry | 10 |

All of the 45 people who voted for Vanilla had Strawberry as the second choice. All 15 people who voted for Strawberry, had Chocolate as their second choice. Of the 40 people who voted for Chocolate, 30 preferred Strawberry over Vanilla, and 10 preferred Vanilla. So, which flavor won? There are multiple ways to interpret this data. Let's look at a couple 👇

Borda Count

In this system for n candidates, each first-place vote receives n points. Second-place receives n-1 points, and so on. The candidate with the most points wins.

Let's compute the points in our example. Vanilla received 45 first places, 10 second places, and 45 third places. So the score for Vanilla is 45n + 10(n-1) + 45(n-2). Here, n is 3, giving Vanilla a score of 200. Here's the final tally:

| Flavor | Points |

|---|---|

| Vanilla | 200 |

| Chocolate | 195 |

| Strawberry | 205 |

Strawberry has won! Strawberry, which had the fewest votes in the Plurality voting system, has the most points in the Borda ranking system. Totally ridiculous, isn't it? Well maybe, but maybe not. Strawberry did receive the fewest third-place votes. And 75% of the people had Strawberry as their second choice. Perhaps Strawberry does deserve to win!

Instant Runoff Voting

Let's take a look at a different model of interpreting the ranked voting data. In an Instant Runoff, the candidate with the fewest first-place votes is eliminated, and its votes are distributed to the second choice. This is then repeated until we have one candidate left standing.

Some consider this model of iterative elimination a bit confusing and thereby not practical. But it's getting wide adoption, including in political elections (San Francisco and Oakland city elections, for example). It is also used to decide the winner of the Best Picture Academy Award.

Let's apply this to our current example.

| Flavor | Votes |

|---|---|

| Vanilla | 45 |

| Chocolate | 40 |

| Strawberry (eliminated) | 15 |

Strawberry is eliminated. Since all Strawberry voters preferred Chocolate over Vanilla, Chocolate gets Strawberry's 15 votes. Chocolate now has 55 votes, a majority. Chocolate has won!

Quick Recap

We have discussed three systems so far, and in our example, we have had three different winners for the same election. You may decide subjectively that one of these systems may be better for the use case you have in mind, or you might think as I did at first: It's all pointless!

The Impossibility

There is a concept in decision theory called the Independence of Irrelevant Alternatives (IIA) which states a voter's preference between two choices x and y, should not depend on any other choices.

This seems like a simple and a good rule to live by and our election systems should live by them as well. Sadly, all the systems we have looked at so far do not abide by this rule.

Let's look at the Plurality system - From the rankings we know that all of Strawberry voters prefer Chocolate over Vanilla. If the choice of Strawberry was not there, Chocolate would have won with 55 votes. But with Strawberry present, Vanilla wins with 45 votes.

For the Borda system, Chocolate is the spoiler. With Chocolate in the picture, Strawberry wins. Without Chocolate, Vanilla wins 55-45.

In the Instant Runoff, Chocolate wins when Vanilla is present but Strawberry wins 60-40 if Vanilla is not.

Arrow's Impossibility Theorem

In decision theory, here are some good things to have in an election or any voting system.

- Independence of Irrelevant Alternatives: which we have discussed and failed to account for so far.

- Nondictatorship: Output should not be based on one individual, the wishes of multiple voters should be taken into consideration.

- Pareto Efficiency (Unanimity): should have a notion of unanimity — If every voter prefers candidate A over candidate B, candidate A should win.

- Unrestricted Domain: Voting must account for all individual preferences.

- Ordering: Each individual should be able to order the choices in any way.

All good rules, don't you think? Let's create the ultimate voting system! But here comes Kenneth Arrow to shatter our hopes.

Arrow's Impossibility Theorem states that in all cases where preferences are ranked, it is impossible to formulate a social ordering without violating one of these rules.

In other words, any democracy that satisfies Unanimity and the Independence of Irrelevant Alternatives, must be a dictatorship! *insert dramatic sound effects*

So yeah, we will always find things to argue about in an election. 😒

Dodging the Impossibility

Since every system is flawed, is it the end of this essay? Unfortunately for you, I, like many of you, noticed this one clause in Arrow's impossibility theorem which provides a way for us to escape this gravity well.

The theorem assumes that we are dealing with a ranked choice voting system. Let's just not rank our candidates. 💡

Here I would remind you, that we're trying to look at voting systems in general, not just political elections.

We have implemented non rank based systems in Software numerous times. Think Netflix, Yelp, Reddit, Tinder. The key as you may have guessed is rating, and not ranking (Tinder being a more specific type of rating - approval voting, which I'll discuss later). A voting system based on rating is usually called Score Voting.

Score Voting

The idea behind score voting is that you give each candidate a score in one or many categories. This score is independent of the score the other candidates receive. Think Diving and Gymnastics in the Olympics. The judges rate each athlete based on form, routine, landings. One with the highest total score wins.

But is this system better? That's subjective but we know it lets us escape the impossibility mathematically, and yet conform to independence, unanimity and nondictatorship rules.

Approval Voting

There's a simpler form or Score Voting - Approval Voting. Think of it as a binary version of the score voting. Each person can give a candidate a score of 0 or 1. In other words one can approve or disapprove any number of candidates.

This is similar to how people vote on dating apps like Tinder. They give prospects a score of 1 by swiping right, and a score of 0 by swiping left.

Strategizing the Ranked Vote

One key advantage for Score Voting and Approval Voting is that it never hurts to vote for your favorite candidate. It may seem obvious and trivial but it's not always satisfied by voting systems. For example, it is common in political elections for people to not vote for the third-party candidate even though the third-party candidate may be the voter's first choice; since you know your candidate is unlikely to win, so vote for one of the top two likely candidates instead.

Let's see how ranked voting could alter the elections in our ice cream flavor example. If 20 of the 45 people who voted for Vanilla strategize and vote for Strawberry over Vanilla (their favorite candidate), they can cause Chocolate to lose.

Before strategizing:

| 1st | 2nd | 3rd | Votes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Vanilla | Strawberry | Chocolate | 45 |

| Strawberry | Chocolate | Vanilla | 15 |

| Chocolate | Strawberry | Vanilla | 30 |

| Chocolate | Vanilla | Strawberry | 10 |

After strategizing:

| 1st | 2nd | 3rd | Votes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Vanilla | Strawberry | Chocolate | 25 |

| Strawberry | Vanilla | Chocolate | 20 |

| Strawberry | Chocolate | Vanilla | 15 |

| Chocolate | Strawberry | Vanilla | 30 |

| Chocolate | Vanilla | Strawberry | 10 |

Score and Approval voting are not immune to strategizing but they do not fall victim to the obvious situations where voting for your favorite candidate can be detrimental for that candidate.

Rating the Systems

We have discussed five different voting systems so far, and definitely there has to be a best one. In reality, situations often fall back to the age old trope — it depends. Some environments do not want to complicate it for the voters, so a score based system is not preferred. A lot of cases an Approval system could replace the Plurality system because of it's simple nature.

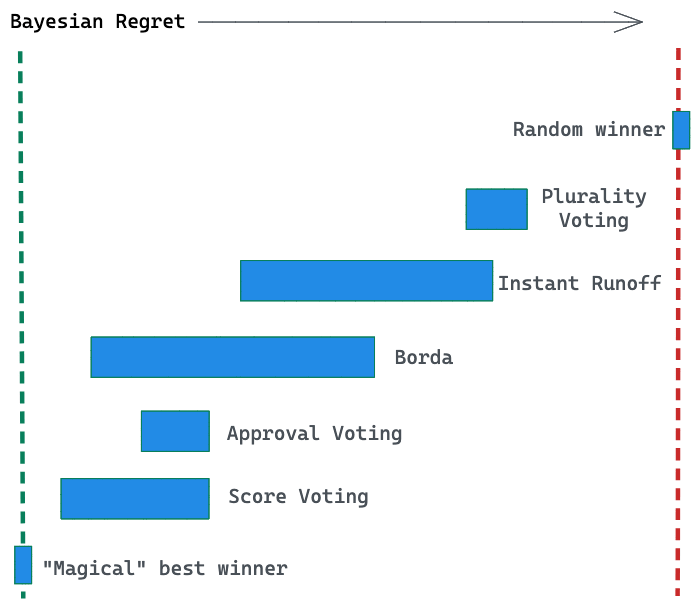

But to rate a voting system means to measure a rating system. How do you measure the 'goodness' of a voting system? One model for doing that is called Bayesian Regret.

Bayesian Regret

The Bayesian regret measures the expected unavoidable human unhappiness caused by a voting system. The more the unpopular candidates get elected, higher the Bayesian regret.

This value is computed using a number of factors: number of voters, number of candidates, the amount of strategizing by the voters, etc. With this, it calculates two features: how much utility society gains from the outcome, and the maximum possible utility the society could have gained from each of the candidates. The difference in these values gives the Bayesian regret. Though I do understand the concept here, I do not know the intricate details in calculating these values.

Mathematician Warren D. Smith studied different voting models, simulating various elections and estimating the Bayesian regret. A lot of it is available on his website rangevoting.org

Here's a rough representation of the data from the simulation:

Each bar represents the range of Bayesian regret values in the election simulations. Lower the value (closer to the left bar) the less the regret.

Here's what we can see from the chart:

- Plurality voting performs poorly regardless of strategizing (the range of values with various strategizing simulated).

- Both the ranked-choice systems (Borda and Instant Runoff) end up with a broad range of regret values, depending on how much strategizing goes on.

- Even with strategizing, Score and Approval voting offer a much smaller range of regret values.

- When voters are honest, score voting gives the lowest regret value.

- The Approval voting system offers a much lower regret value than the Plural system, and yet is equally simple in design.

Conclusion

No voting system is perfect, but the design of the voting system has a huge impact on the winner of the election. Our most common voting system - Plurality voting has a set of serious flaws. It can create spoilers, is least expressive for voters, bad mathematically, predicts higher regret values.

Approval and Score voting add a huge value over the rank-based voting systems.

I am no expert on the topic, but this is what I have learned, found interesting, and have put into a blog post.